By Florence Miller, 29th February 2016

Late last year, Collaborate published their second report on A New Funding Ecology in partnership with the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the Big Lottery Fund. It prompted EFN to start thinking: what do we know about the ecology of the funders who support environmental causes? What niches do they occupy and how are they connected? Which niches are crowded and which ones are occupied by few funders? Does it matter? Would it be useful, as a funder, to know who occupies very similar or very different niches from you?

EFN has long been interested in mapping out funding patterns in an effort to make the invisible visible and help funders make better-informed decisions about their grantmaking. Through our Where the Green Grants Went series, we have mapped out funders by both the issues they support (biodiversity preservation, climate change and so on) and the geographies in which they operate, identifying gaps as we went. What we’ve never done is map out funders according to their theories of change. How many funders think that influencing political elites is the most effective way to effect change, and channel their funds accordingly? How many support the creation of ‘better’ businesses for the same reasons? Which theories of change do the individuals behind the grantmaking institutions – the trustees and staff – espouse, and are their personal beliefs reflected in their grantmaking?

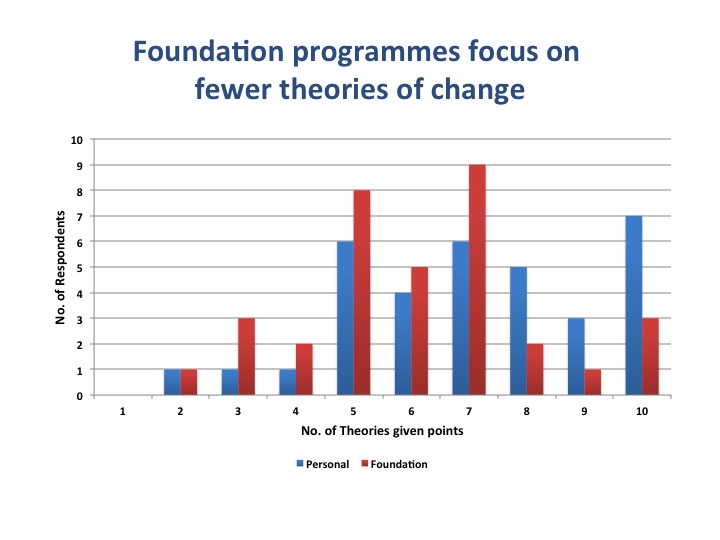

Adapting a taxonomy of ‘theories of change’ developed by the Campaign Lab, we asked members of EFN attending our annual Retreat to allocate 100 points next to the theories of change they most identified with personally, and then to repeat the exercise reflecting their trust’s actual grantmaking. They could allocate the 100 points however they liked – lumping them all next to one theory of change, or spreading them across several.

The theories of change we settled upon are described at the foot of this post. This was an experiment, and we were aware that we hadn’t perfected the theories and that those participating would have plenty of feedback for us about how they could be improved (they did!). But the research EFN has conducted in the past, in the form of Where the Green Grants Went and Passionate Collaboration, has always started somewhat experimentally and it has generally turned out to be very useful to the field, so we ploughed ahead.

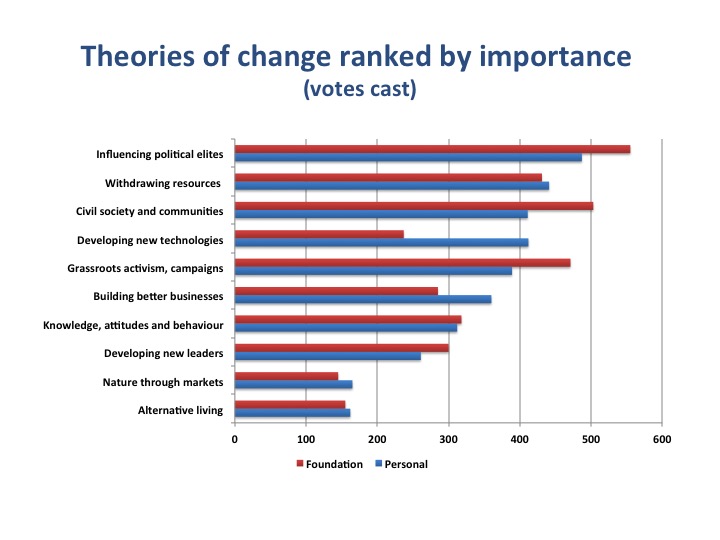

The results whet our appetite to dig deeper. Of the 30 or so funders who responded to the survey, ‘influencing political elites’ scored highest for both funders’ personal responses and their responses reflecting their actual grantmaking (see below). That was particularly interesting in the light of Passionate Collaboration, in which environmental NGOs listed advocacy as the approach that most needed more resources in the sector. In other words, funders think influencing political elites is a top priority but NGOs don’t feel they’re getting as much resource to do this as they need.

The second most favoured theory of change for funders personally – and fourth for their grantmaking – was ‘withdrawing resources from the current system’. This implies strong support for such approaches as markets-based campaigns, corporate boycotts, fossil fuel divestment and new economic approaches. Does that accurately reflect grantmaking patterns? We are not convinced, but were interested to see that levels of interest, at least, are high in this area.

The second most favoured theory of change for funders personally – and fourth for their grantmaking – was ‘withdrawing resources from the current system’. This implies strong support for such approaches as markets-based campaigns, corporate boycotts, fossil fuel divestment and new economic approaches. Does that accurately reflect grantmaking patterns? We are not convinced, but were interested to see that levels of interest, at least, are high in this area.

Further down the rankings, we discovered that collectively funders personally set more store by ‘developing new technologies’ and ‘building better businesses’ than was the case for their grantmaking programmes. Meanwhile, the responses reflecting their foundations’ giving prioritised ‘grassroots activism and campaigning’ more than they did as individuals. Are foundations – counterintuitively – more radical than the individuals behind them? Or did this simply reflect the fact that funders think building better businesses and technological innovation are important but should come about with commercial, not philanthropic, funds?

Another surprising finding was how poorly rated ‘protecting nature through markets’ was as a theory of change, suggesting that the funders surveyed did not set much store either by purchasing land to protecting it or by ecosystem services-based approaches to conservation. From Where the Green Grants Went, we know that biodiversity and species preservation receive a quarter of all UK philanthropic funds, so we expected this category to have a stronger response. What became clear was that we had not accurately captured the theories of change behind much of this conservation work in our taxonomy. We’d love to hear how you characterise the theory of change behind your conservation work in the Comments section below.

What really got our EFN research juices flowing was the disparity between the spread of funders’ personal responses and the responses reflecting their actual grantmaking (below). Individuals spread their bets a bit more, favouring many different theories of change (several people awarded points to all ten theories of change, and almost all individuals awarded points to five theories or more). Foundations were much narrower in the actual focus of their grantmaking. No surprises there – we would expect foundations to focus in and prioritise the sorts of approaches they support.

But what would we find if we conducted this survey for a much bigger cohort of environmental grantmakers? Is it possible that foundations are coalescing around particular theories of change, perhaps because funders tend to be influenced by each other as well as by the zeitgeist, and that that clustering process is leaving some key approaches neglected?

Certainly it seems that the individuals behind environmental grantmaking operations think we need to be supporting a range of approaches – to create a movement that better reflects a fully functioning ecosystem in which many niches are occupied. Wouldn’t it be useful to know if there are gaps?

Florence is EFN’s Coordinator.

THEORIES OF CHANGE

borrowed with thanks and adapted from work by the Campaign Lab

BUILDING BETTER BUSINESSES

We have to influence the economy to effect change. Supporting the development of new business models and ensuring their take-up is the best way to do this.

e.g. Fairtrade and organic certification, B corporations, the circular economy

ALTERNATIVE WAYS OF LIVING

Our current ways of living are ‘broken’. Creating alternatives is the only option. “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

e.g. communal living, off-grid subsistence livelihoods, Dark Mountain project

CHANGING KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES AND BEHAVIOUR

Many of the problems we face stem from individuals’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. Change can best be achieved by modifying these.

e.g. environmental education, Meatless Mondays, “I am not a plastic bag”, change your light bulbs

DEVELOPING NEW TECHNOLOGIES

Investing in new technological developments holds the greatest promise in terms of a more sustainable use of resources.

e.g. renewable energy and battery technologies, water management systems, electric vehicles

INFLUENCING POLITICAL ELITES

Government policy has the broadest impact on society; influencing political elites is therefore the best way to effect change.

e.g. advocacy and lobbying to achieve legislation such as the Climate Change Act, or regulatory reforms

WITHDRAWING RESOURCES FROM THE CURRENT SYSTEM

We have to influence the economy to effect change. The best way to do this is by withdrawing the resources on which it depends, such as labour, capital, and social licence to operate.

e.g. fossil fuel divestment, the sharing economy, corporate boycotts

PROTECTING NATURE THROUGH MARKETS

The market is our most powerful tool for change. Individuals and institutions can best protect nature by working through the market and ascribing monetary value to it.

e.g. Natural Capital Coalition, purchasing land to conserve it, ecosystems services approaches

DEVELOPING NEW LEADERS

To change the world we need to identify strong leaders and empower them to work with many stakeholders. Investing in individuals is key.

e.g. LEAD International, Conservation Leadership Programme, Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership

GRASSROOTS ACTIVISM AND CAMPAIGNING

Mobilising the grassroots is the most effective way to generate the political will needed to disrupt the status quo.

e.g. People’s Climate March, Occupy, Frack Off, Stop Heathrow Expansion

FOSTERING CIVIL SOCIETY AND COMMUNITIES

We will achieve the change we seek by establishing better social institutions that guarantee democracy, equity, and the fair allocation of resources.

e.g. Transition Towns, faith-based networks, community organisations

Keywords: effectiveness, funding overseas